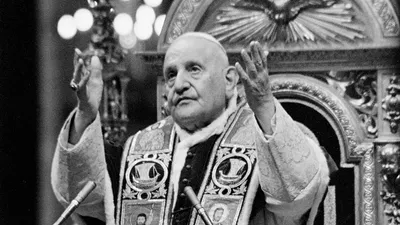

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) is widely regarded by historians and Christians as a pivotal moment when the Pope’s traditional authority waned, marking a critical juncture in the history of the Catholic Church. This council transformed the Church from a strictly scriptural institution—one historically critical of Jewish Jihad—into a more politically oriented entity, increasingly aligned with Jewish interests over biblical teachings. Among other changes, the council censored aspects of the Church’s theology to align with these interests.

Notably, the Second Vatican Council removed entire biblical verses critical of Jews, their role in the crucifixion of Jesus, and references to money or other disparaging terms from Church publications. These changes empowered bishops and weakened the papacy, aligning with a post-World War II Jewish agenda to curb "authoritarianism" within the Church.

This shift is significant because it marked the culmination of a nearly thousand-year effort by Jewish groups to either convert or subvert the Catholic Church. Contrary to common narratives that frame the Second Vatican Council as a response to post-Holocaust reforms, it was, in fact, the climax of a millennium-long Jewish effort to conquer the Church theologically. The council’s outcomes, enacted in 1964–1965, represented a bloodless victory for these efforts, fundamentally altering the Church’s stance without physical conflict.

The Roots of Jewish Influence: Maimonides and the Crusades

The seeds of the Second Vatican Council were planted as early as the 12th century by influential Jewish rabbis, particularly Rambam, also known as Maimonides (1138–1204). A Sephardic rabbi, philosopher, and Kabbalist, Maimonides was one of the most prolific Torah scholars of the Middle Ages. He served as a preeminent astronomer and physician, notably as the personal doctor to Saladin, the Muslim defender of Al-Quds/Jerusalem during the Crusades. Born in Córdoba, al-Andalus (modern-day Spain), Maimonides later relocated to North Africa, living in Morocco and Egypt, where he worked as a rabbi, physician, and philosopher. Culturally Arab, he was a Jewish nationalist in spirit and intellect.

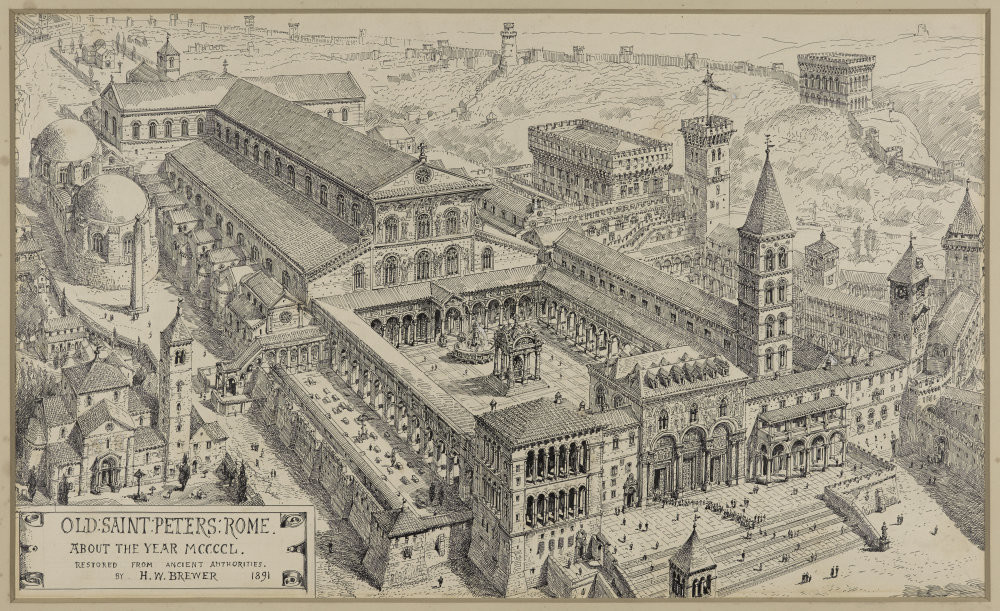

During the Crusades, as Muslims and Christians waged war, Jews found themselves caught in the middle—not because either side demanded their allegiance, but because Jewish leaders sought to advance their own interests independently. A core Jewish objective was the reestablishment of an ancient Jewish Caliphate in Palestine, a modest ambition compared to the vast territories controlled by Muslims and Christians, both younger faiths than Judaism. To achieve this, Jewish emissaries repeatedly approached the Pope and Christian kings, requesting soldiers and mercenaries to help reclaim Palestine, establish a Jewish Caliphate, build the Third Temple, and usher in the messianic era—an outcome that would also serve Christian interests by heralding Jesus’ return. However, Christian leaders consistently rejected these proposals, fearing betrayal by Jewish radicals after achieving their goals.

Frustrated by these rejections, Jewish rabbis, led by figures like Maimonides, turned to Practical Kabbalah, employing mystical strategies and manipulations to influence Rome. They prophesied that a new Messiah, named Moshe (Moses), would appear in Rome, performing miracles to bring the Pope to his knees. They posed a critical question: Why would the Jewish Messiah appear in Rome rather than Jerusalem? Their answer was that the Pope represented a modern Pharaoh, akin to the biblical oppressor of the Jews. Just as Moses confronted the Pharaoh with plagues and cosmic displays, the new Moshe would make Rome tremble, ultimately defeating the Pope and converting him to Judaism, heralding the messianic moment. For Jewish Jihadist mystics, this daring proposition was as straightforward as child’s play.

Early Attempts to Conquer Rome

The first attempts to conquer Rome—either by converting the Pope or unleashing divine plagues—were led by self-proclaimed Jewish Messiahs claiming miraculous powers. One such figure was Abraham ben Samuel, known as Abulafia (1240–1291), a Kabbalist and self-styled Jewish Messiah. According to Jewish tradition, a Messiah must crush the enemies of the Jewish people through force or miracles. Convinced of his abilities, Abulafia believed he could deploy both methods to achieve his goals.

Initially, Abulafia sought to raise an army to establish himself as the Jewish King. He set out to find the mythical River Sambation, a legendary waterway in Jewish lore said to lie in the East, accessible only on the Sabbath. Beyond this river, according to myth, lay immense riches and the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, awaiting the Messiah’s call. Abulafia’s failure to locate the river dashed his hopes of recruiting a Jewish Jihadist army.

Undeterred, Abulafia followed Maimonides’ model, which suggested that a Moses-like figure is reborn in every generation. He embarked on a decade-long journey to Rome, arriving during Rosh Hashanah—a significant time for messianic revelation—with the mission to convert Pope Nicholas III to Judaism. Abulafia’s strategy was simple: converting the Pope, who wielded authority over half the world, would expedite the Messiah’s coronation as a global king, bypassing the need to build an army or infrastructure in Jerusalem. A bloodless Jewish Jihad revolution within Christianity would make the transition to the messianic era swift and seamless.

To achieve this, Abulafia employed complex Kabbalistic rituals, including prayers, fasting, wearing specific garments, and performing psychological maneuvers to gain mystic powers. He believed these acts would earn divine favor, granting him the ability to defeat the Pope, whom he viewed as the new Pharaoh. However, Pope Nicholas III, well-versed in biblical narratives and wary of Jewish messianic ambitions, learned of Abulafia’s intentions in advance. Prepared for the Kabbalist’s arrival, the Pope successfully thwarted Abulafia’s plans, ending his mission in failure.

Persistence and Ultimate Success at Vatican II

Despite repeated failures, Jewish efforts to convert the Pope or subvert the Church continued for centuries, each attempt ending in defeat until the Second Vatican Council in 1962–1965. At this summit, Jewish groups achieved a significant victory by influencing the Church to revise its teachings, particularly regarding the role of Jews in Jesus’ crucifixion. This marked the partial fulfillment of their millennia-long quest, celebrated as a triumph by Jewish advocates.

This claim is supported by Malachi Martin’s insider exposé, The Pilgrim (1964, published under the pseudonym Michael Serafian), which critiques the Second Vatican Council’s handling of the “Jewish question” and broader Church reforms. As a Jesuit priest and scholar who served as secretary to Cardinal Bea during Vatican II, Martin had firsthand knowledge of the council’s processes. His linguistic skills, including fluency in Hebrew, and connections with Jewish intellectuals like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel positioned him as a key participant in discussions about Jewish efforts to alter Christian doctrine. Initially viewed as a liberal supportive of ecumenical dialogue, Martin was privy to plans that he later criticized for their disregard for Christian theology.

In The Pilgrim, Martin, writing as Serafian to protect his position within the Jesuit order and avoid accusations of anti-Semitism, argued that the council was manipulated by external Jewish interest groups. These groups pushed the Church to adopt pro-Jewish and pro-Israel positions, abandoning its traditions and theology. Martin expressed concern that the council’s efforts to revise the Church’s stance on Judaism, particularly through drafts of Nostra Aetate (“In Our Age”), lacked theological precision. He believed the document failed to clarify the relationship between the Old Covenant (Judaism) and the New Covenant (Christianity), leaving unresolved questions about Judaism’s role in salvation history. While acknowledging the moral necessity of absolving Jews of collective guilt for Jesus’ death, Martin worried that the framing risked downplaying Christ’s centrality in Catholic theology, as early drafts avoided explicit references to conversion or the fulfillment of Jewish covenants in Christianity.

The Lasting Impact of Vatican II

Since the Second Vatican Council, every newly elected Pope, including Pope Francis, has held symbolic rather than authoritative power, as the Church’s traditional doctrines were significantly altered. The council’s decisions, particularly on the contentious issue of the Jewish people, removed the Pope’s ability to independently interpret Church doctrine. This shift also influenced broader changes, such as Pope Francis’ evolving views on gay marriage and LGBTQ issues. Having amended its stance on Jews, the Church found itself compelled to accommodate other groups, transitioning from a metaphysical institution with rigid values to a philosophical one with a more flexible ethos. The teachings of previous Popes, rooted in the Gospels, no longer applied to the post-Vatican II Church, which became subject to the influence of powerful external forces.

Why This Mattered to Jewish Jihadists

Why did Jewish groups invest millennia, along with significant political and financial capital, in this pursuit? As one Jewish scholar paraphrased, “Our struggle with Islam is about land; with Christianity, it is spiritual.” This spiritual conflict stems from the Jewish rejection of Jesus’ centrality to Catholic theology—both his divinity, which contradicts Jewish tenets, and the accusation of Jewish responsibility for his crucifixion. The deicide charge—the doctrine holding Jews accountable for Jesus’ death—was a cornerstone of Catholic teachings for centuries, and Jewish leaders sought to dismantle it. Their objection was not merely emotional but strategic: as long as Christians were taught that Jews were responsible for Jesus’ death, broad Western support for a Jewish state remained elusive.

The trauma of original sin pales in comparison to the impact on Christians when reminded by their Church that Jews played a role in Jesus’ crucifixion. During the Dark and Middle Ages, this belief fueled rhetorical and sometimes physical confrontations between Christians and Jews. Had the Second Vatican Council not occurred, this dynamic might persist today. While elites and ruling classes might still support Israel for strategic reasons, many Catholics would likely oppose it, driven by theological convictions rooted in pre-Vatican II teachings.